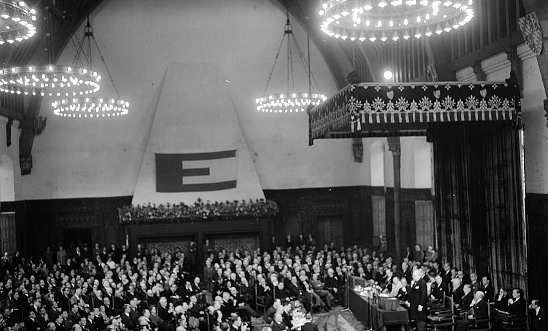

Europa Congress in The Hague, May 1948" width="548" height="331" />

Europa Congress in The Hague, May 1948" width="548" height="331" /> Europa Congress in The Hague, May 1948" width="548" height="331" />

Europa Congress in The Hague, May 1948" width="548" height="331" />

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is an international human rights treaty between the 47 states that are members of the Council of Europe (CoE) - not to be confused with the European Union.

Governments signed up to the ECHR have made a legal commitment to abide by certain standards of behaviour and to protect the basic rights and freedoms of people. It is a treaty to protect the rule of law and promote democracy in European countries.

The idea for the creation of the ECHR was proposed in the early 1940s while the Second World War was still raging across Europe. It was developed to ensure that governments would never again be allowed to dehumanise and abuse people’s rights with impunity, and to help fulfil the promise of ‘never again’.

In May 1948 after the war had ended, the ‘Congress of Europe’ was held in The Hague, a gathering of over 750 delegates which included leaders from civil society groups, academia, business and religious groups, trade unions, and leading politicians from across Europe such as Winston Churchill, François Mitterand and Konrad Adenauer.

In his speech to the Congress, Churchill stated:

“In the centre of our movement stands the idea of a Charter of Human Rights, guarded by freedom and sustained by law.”

Winston Churchill, (The Hague, 7th May 1948)

It was from this gathering that the ECHR began to take shape. The assembly proposed a list of rights to be protected, and also drew a number of articles directly from the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

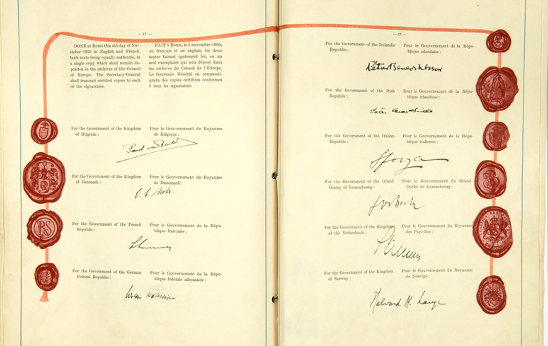

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) was formally drafted by the Council of Europe in Strasbourg during the summer of 1949. Over 100 members of parliament from across Europe assembled to draft the charter. The United Kingdom was the very first nation to ratify the convention in March of 1951.

“We desire a Charter of Human Rights guaranteeing liberty of thought, assembly and expression as well as the right to form political opposition. We desire a Court of Justice with adequate sanctions for the implementation of this Charter.”

From ‘Message to Europeans’, (The Hague, 10th May 1948)

The ECHR came into full effect on the 3rd September 1953. It was intended to be a simple, flexible roundup of universal rights, whose meaning could grow and adapt to society’s changing needs over time. Not only were ordinary people to be protected from abuse by the state, but duties were to be placed on those states to protect individuals. It has been hugely important in raising standards and increasing awareness of human rights across CoE member states, and beyond.

The creation of the ECHR led to the establishment of the

Until 1998, the only way UK citizens could bring a legal challenge relying on their rights under the ECHR was to go the European Court of Human Rights, and this process could be lengthy and expensive. The Human Rights Act (HRA) allows the rights guaranteed by the ECHR to be enforced in UK courts – increasing everyone’s access to justice in this country.

The Human Rights Act brings the ECHR into British Law, meaning that judicial decisions on human rights cases can be reached within the domestic legal system, building up a body of specifically domestic case law to refer to in the future.

The HRA has two parts: the second part contains most (but not all) of the rights from the ECHR, taken word for word. The first part sets out how those rights are to be applied and enforced. To find out more about how the HRA affects law making and public authority decision taking, and how it can be enforced, please read our Human Rights Act FAQ.

Successive governments have expressed an intention to repeal the HRA and replace it with a less protective Bill of Rights. While there are no active plans to do so that we are aware of, this remains a threat. Please sign our petition to Save The Act.

Article 1 – obligation to respect human rights

The state has the responsibility to respect every individual’s human rights, as set out in the Convention itself.

Article 2 – right to life

We all have the right to life, and not be killed by another person.

The state must protect people’s lives by enforcing the law, protecting those in danger, and safeguard against accidental deaths.

Article 3 – prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment

Nobody, under any circumstances, can torture or abuse anyone else. We should never be treated in ways that cause us serious physical or mental suffering.

Article 4 – prohibition of slavery and forced labour

Nobody should ever be made a slave or forced to work against their will.

There are minor exceptions to this article, for example in some cases it is legal to require someone to work in if they’re in prison or the military services.

Article 5 – right to liberty and security

We can only be detained in certain circumstances, for example if we’ve been convicted by a court, or if we’re considered to be a danger to ourselves.

Article 6 – right to a fair trial

We have the right to a fair and public trial, within a reasonable amount of time, by an independent and unbiased judge.

If charged with an offence we should be assumed innocent until proven guilty.

Article 7 – no punishment without law

All crimes should be clearly defined by the law. We can only be found guilty of a criminal offence if there was a law against it at the time the act was committed. Once found guilty of a crime we cannot later be given a heavier sentence.

Article 8 – right to respect privacy and family life

This right exists to protect four things: our family life, our home, our private life, and our correspondence.

We have the right to live with our family and our loved ones.

Respect for the home guards against intrusion into where we live, or to protect us being forced from where we live without good reason.

Respect for private life protects our personal freedoms, including respect for our sexuality, the right not to be placed under unlawful surveillance, or for us not to have personal information spread about us against our will.

Respect for correspondence allows for us to communicate with others freely and in full privacy.

Article 9 – freedom of thought, conscience and religion

We all have the right to hold religious and other beliefs. We also have the right to change these beliefs when we choose. We should be free to worship and express our beliefs both in public and private spaces.

Article 10 – freedom of expression

We have the right for us to hold our own opinions, to express our views and ideas, and to share information with others.

This article can protect our right to express views that some may find unpopular or offensive.

Article 11 – freedom of assembly and association

We have the right to join with others to protect our common interests, to form trade unions political parties.

Importantly this article also exists to protect our right to hold meetings, and to assemble in groups to peacefully protest.

Article 12 – right to marry

We have the right marry who we want to, and to start a family.

Article 13 – right to an effective remedy

If our rights are violated then we must be able to challenge this through legal means. The state must make arrangement for this, and there may be compensation for any damage caused to us.

Article 14 – prohibition of discrimination

Our rights should never be denied to us due to any form of discrimination, whether due to our ‘sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status’.

Article 15 – derogation in time of emergency

A state can choose to ignore some specific rights in the ECHR at a time of war or other emergency threatening the life of the nation, but any removal of rights should be limited to those absolutely required by the situation. A state must always make sure these measures are consistent with its obligations under International Law.

Article 16 – restriction on political activity of non-nationals

A state can restrict the political activity of non-nationals, but this does not apply to the nationals of EU member states when in an EU country.

Article 17 – prohibition of abuse of rights

Nothing in the ECHR allows for any state, group or individual to destroy the rights and freedoms that the convention protects.

Article 18 – limitation on use of restriction of rights

The restrictions allowed by the convention should not be applied for any other purpose than those explained in the convention itself.

The Convention also contains a list of protocols which make amendments to the original articles. These relate to the right to property, education, free elections and many other issues. To read more detail about the ECHR take a look at the Council of Europe’s webpages for PDF versions of the Convention and Protocol.

Article – the substance of a treaty or agreement.

Council of Europe – The Council of Europe (CoE) was formed in 1949 as a way of encouraging cooperation between countries in Europe after the Second World War. It is not related to the European Union. There are 47 members of the CoE compared to the EU’s 28. The UK became a member of the CoE at its inception in 1949, some 24 years before joining the EU. The UK’s membership of the Council will be completely unaffected if it exits from the EU.

ECHR - The European Convention on Human Rights

ECtHR - The European Court of Human Rights

Treaty – this is an agreement between states that has been ratified and formally concluded.

Protocol – a treaty that supplements or adds to an existing treaty.

Ratification - A state notifies the other parties that they consent to be bound by a treaty. This is called ratification. The treaty is now officially binding on the state.

Signing - By signing a treaty, a state expresses the intention to comply with a treaty. However, this expression of intent is not binding on its own.